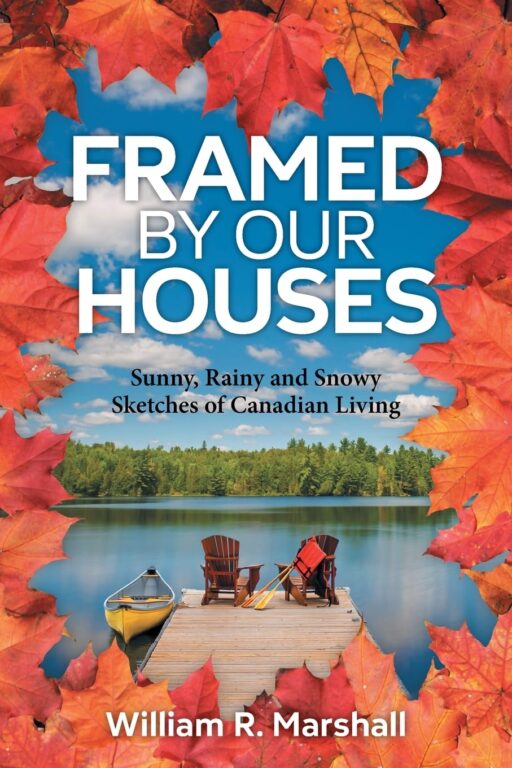

Sunny, Rainy and Snowy Sketches of Canadian Living

by

What’s it like being the only Anglophones settling into the rural Beauce region south of Québec City, where no one keeps a lock on their door? What kind of struggles does one encounter as a young adult living in communal housing in Peterborough, Ontario in the era of love, peace, and rock and roll? How does it feel to eke out a rugged living in a remote cabin in Brighton Beach, BC, without any experience of that lifestyle?

Author William R. Marshall can tell you the answers, since these are all lives he’s lived. Full of warmth, heart, and a delightful sense of humour, Framed by Our Houses is a gorgeous collection of stories of Marshall’s time spent in different houses across Canada, from farm to sea and city.

You do so much important stuff in your first three years. Like learning to walk and talk and play and wearing your last poopy diaper. You think you'd remember something. Why it is that you can't remember anything important you did before you were three? My mother tells me that the first house I lived in, from birth to age three or so, was on Whetter Avenue. I do not remember a thing about it.

For a short while, my parents rented an upstairs apartment on Duchess Avenue, the only recollection I have of it being some very scary open stairs on the outside of the building. To this day, I do not like such stairs.

READ MOREThe first house I actually remember living in was in a newer area of north London, near the University of Western Ontario and just a block north of the Stevens' homestead. It was a newly built house, small and square and white. I could crawl through the milk box. Remember those? A small cubby with a little door on the outside and another on the inside, just big enough for an elf.

The house faced a ragged field that led to the Thames River and dense woods along the banks. In the summer time, a bridge made of barrels would be wired across the river to give our neighbourhood access to Gibbon's Park and its swimming pool, on the other side. A big tree hung over the bank with a tempting swinging rope on it. Every kid needs one of those.

My father finished the painting in the house and then built a recreation room in the basement. It was a wonderful place. It was painted black, everywhere, and we cut out potatoes with designs on them and dabbed bright fluorescent colours all over the floor and walls. Hand-prints, too. Tiny starlights on the ceiling. An obligatory bar in the back and a plastic garden thing at the other end. Quite a sight, I'm sure, but it was "in" back then.

For me and my friends the rec room was the command centre of our space station. Foil-covered cardboard boxes were our space and robot suits. TV rabbit ears, our antennae. A Morse code practice pad with flashing light, click or buzz sound choices was our Communications centre.

Having convinced all the families on the block to buy the same gauge of model railway, our rec room also became Treasure Island—with a massive railway system, of course. Once we had assembled every kid's tracks and trains and transformers, added the smoke drops to the engines' stacks, dimmed the lights and cranked up the trains... we were transported to Never Never Land. One train started in the low beach area and rose up over the sofa (the highlands), through the curtains and up to the furnace and hot water heater (the mountain top, the Indian village) then down to the laundry tubs and over the tool bench (the heartless city of adults) and on to the plastic garden and back to the lowlands by the sea and Captain Hook.

By the time I was eleven or so, my mom had repainted the floor and added those foot-print silhouettes for all the dance steps. She would teach me and my boy friends how to dance. We even had a few sock hops there, with real girls, too.

That's what happens when you outgrow your train set, I guess. My father built a rec room in every house we owned after that.

COLLAPSE